by Jeff Bratzler, CFP

The financial costs of long-term care add to the burden of 5 million cancer patients, 4 million Alzheimer’s victims, 5 million heart disease victims and millions of others afflicted by Parkinson’s disease, strokes and other debilitating conditions. What are the best strategies to avoid dependence, protect assets, maintain our standard of living, and guarantee access to care?

What is Long-Term Care?

60% of all Americans who reach age 65 will need long-term care.

The inability to function independently can result from either physical or mental limitations and is defined in terms of essential “Activities of Daily Living.” Long-term care services include:

Personal care such as bathing, dressing, transferring, feeding

Household chores such as meal preparation and cleaning

Transportation to doctors, care centers and daily activities

Medical services such as ventilators, intravenous drug therapy or physical therapy

Long-term care is provided in many different settings including the home, community centers, and institutional (continuous care) facilities such as assisted living and nursing homes.

A woman age 65 has a 1 in 3 chance of staying in a nursing home

for a year or more. A man age 65 has a 1 in 7 chance.

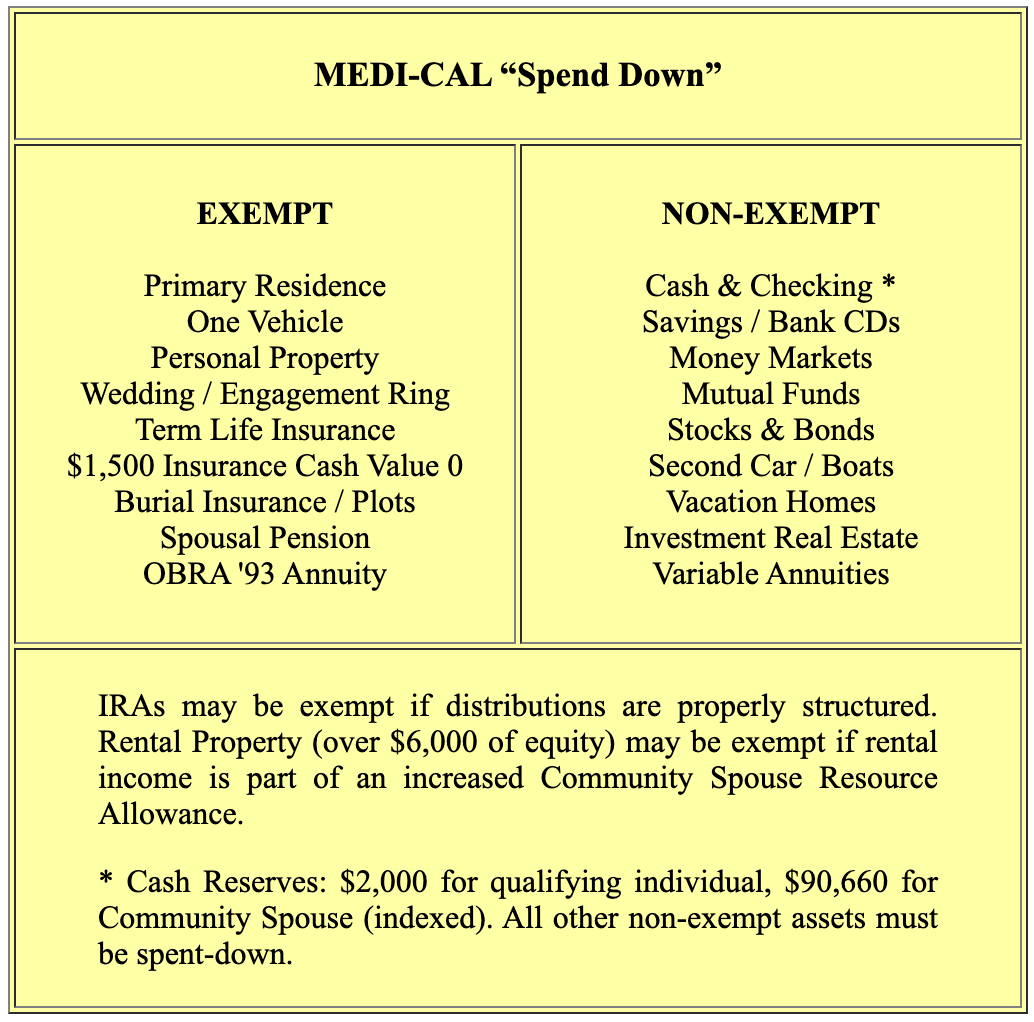

SELF-INSURING

The average nursing home stay is 2.8 years (average cost: $126,000). 21% of those who enter a home will stay over 5 years (average cost: $225,000). Alzheimer's patients generally stay 8 years (average cost: $360,000). Medi-care or traditional health insurance will pay only 5% of these costs. As a safety net, Medi-Cal requires the “spend down” of non-exempt assets (see box). Early on, family members may be counted on to provide limited care at home. But round-the-clock care is often necessary as an illness progresses. A family member might be forced to leave a career – which only compounds the financial burden.

LONG TERM CARE INSURANCE

These policies insure against the costs of care when an individual loses the ability to function independently, whether the inability occurs due to an injury, illness or the natural progression of aging.

Coverage is usually comprehensive, encompassing both home and institutional care. The premium is determined by the applicant’s age (and health) at the time of purchase, making the question of “when to buy” often the most critical. For a “standard” policy of $130 daily benefit ($65 for home care), lifetime benefit period, 90-day waiting period, and 5% inflation option, a 70-year-old faces premiums about double that of a 50-year-old. Waiting “avoids” 20 years of payments, but the 70-year-old may not be healthy enough to qualify for any coverage at all.

Careful policy design can significantly reduce premiums. Lowering the benefit period from lifetime to 3-years makes sense for many families. The inflation option, on the other hand, is usually a must. Historically, the average cost of nursing home care has increased 6.7% annually. An average cost of $130 per day would soar to $476 per day 20 years from now.

“Long-term care insurance costs too much” is rapidly becoming a pennywise, pound-foolish objection. Given the trends in life expectancy and the statistical probability that someone in your family will require long-term care, relative costs are not that expensive. A couple in their early 70’s may pay $3,000 -$ 4,000 annually for coverage, but that amount may not “self-insure” a month of nursing-home care.

ASSET PROTECTION

Most people believe they must spend down their entire life savings before they can qualify for Medi-Cal assistance. This is not true. The state of California cannot impoverish or cause undue financial hardship on the Community Spouse: the healthy spouse who remains at home when the ill spouse is admitted to a nursing home or similar long-term care facility.

Medi-Cal qualifying requires strict adherence to complex rules. You cannot give away excess assets within 30 months of Medi-Cal qualifying without incurring a period of ineligibility during which you must pay all the bills. Federal law has established criminal penalties against those who “for a fee knowingly and willfully counsel or assist an individual to dispose of assets in order for the individual to become eligible for Medicaid, if a period of ineligibility is imposed upon the applicant.”

The purchase of an annuity to qualify for Medi-Cal does not create a period of ineligibility if the annuity complies with the OBRA ’93 guidelines. The purchase of an immediate annuity (including one with guaranteed period-certain provisions) converts non-exempt assets (cash, bonds, stocks) into an exempt asset. Medi-Cal only looks to the income from the annuity to go toward share of cost.

Whether an annuity strategy is advisable depends on the circumstances. Assets can be “spent” to payoff the home mortgage, make home improvements, pay bills, or purchase a new car. If the community spouse has total monthly income below $2,267 (indexed) allocating income to reduce the ill spouse’s share of cost, or increasing the community spouse’s resource allowance, may be better strategies. The rules are complex. A good advisor will help you evaluate these options.

“SHARE OF COST”

85% of nursing home residents receive Medi-Cal assistance, but only 17% of them start out that way. For many families, the primary purpose of Medi-Cal qualifying is to cap the costs at the Medi-Cal rate, which is usually 20% - 40% less than the care facility’s full “private-pay” rate (the amount families pay if they have long-term care insurance or spend-down personal assets). But an ill spouse who receives care and pays the entire Medi-Cal approved rate is not incurring liens, despite saving $1,000 - $2,000 per month in overall costs. Level of care does not diminish by switching to Medi-Cal. Strict laws prohibit treating patients differently based on method of payment.

MEDI-CAL RECOVERY

Advanced legal planning may prevent Medi-Cal from recovering against the family residence. Beware of shared ownership, because the state could make a claim against the adult-child’s interest, not just the interest owned by the institutionalized parent. Wills, living trusts, and property deeds should be reviewed. This is an important step not only to reduce Medi-Cal Recovery but also to prevent the loss of Medi-Cal benefits when an institutionalized spouse inherits a deceased spouse's property. Such assets must be spent-down (to the $2,000 limit) before Medi-Cal benefits can resume. With no way to make the assets exempt, the care facility effectively becomes the beneficiary of the estate.

HELP IS NEAR

There is a great deal of misinformation on long-term care, so be careful:

Contact BCN at 1 (800) 876-1088 if you have further questions. Our long-term care specialists will carefully evaluate your needs and make specific recommendations.

Contact BCN if you have questions, concerns or need planning strategies related to any of your benefits.